|

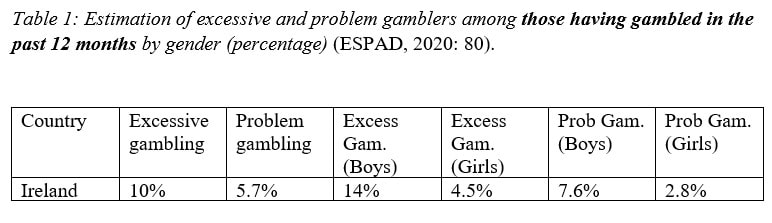

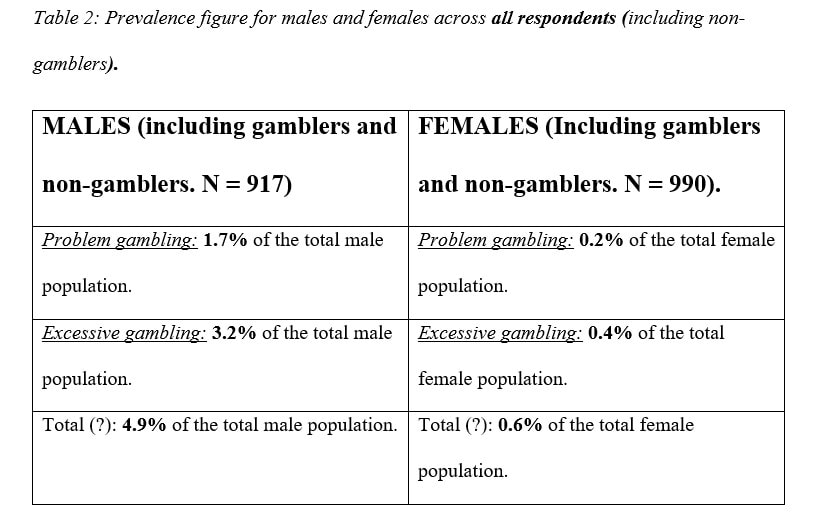

Barry Grant: As a person working for an NGO, which advocates for safeguarding measures to be put in place to protect vulnerable adults and children from gambling related harm, I sometimes get the occasional snarky comment directed my way. It's often something along the lines of, 'Won't somebody please think of the children?!' - a much-used quote from the Simpsons. I respect everyone's opinions on these matters and I'm more than happy to debate my side of the street with anyone who is so inclined. I'm very comfortable with my pearl-clutching, bleeding-heartedness - as I witness, first-hand, on a daily basis, the devastation which a lack of gambling regulation and harm-prevention services has on individuals, families and the wider community. The vast majority of people who attend our gambling addiction treatment service, started gambling as children. Of all the massive gaps in problem gambling service provision, which I find utterly infuriating, the one that boils my blood the most, is the absence of any statutory intervention to "take appropriate measures to protect young people from gambling-related risks". The reason that last section is in quotes, is that it comes from the National Policy Framework for Children and Young People, 2014-2020 (Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures). The policy is in its final year and, to date, the only change which has the potential to have any positive impact on children and young people is the legislation enacted this year, which places an over-18s age restriction on Tote betting and on 'gaming' machines. Previously there had been no age limit at the Tote and 'gaming' machines (such as slot machines - the most addictive form of gambling) had an age limit of 16. Government has completely ignored its duty of care to young people, when it comes to gambling-related harm. We know, from the recent European School Survey (ESPAD) of 15-16 year old's in Ireland, that betting on sports or animals (horse and dog racing) is the most common gambling activity. This can only happen if gambling operators are failing to verify the age of their customers. We also know that when the Regulator of the Irish National Lottery performed a 'Mystery Shopper' test in July 2018, they found that over one-third of retail staff (37%) did not attempt to verify the young person's age. A recent PQ reply from Minister for Health, Stephen Donnelly, showed that the State has never funded any harm-prevention interventions for gambling addiction. In the recently released ESPAD survey, they looked at problem gambling among 15-16 year old's for the first time. While they did publish rates of problem gambling among those who gambled, they did not provide the prevalence rate, across all respondents. As I am terrible at maths and get nose-bleeds when it comes to statistics, I reached out for help. Doctoral Student, Conor Keogh (UCD) came to the rescue. Here are the headline figures from Conor's analysis of the ESPAD Survey (2019) and a comparison with the National Advisory Council on Drugs and Alcohol (NACDA) problem gambling prevalence rates from 2014/15:

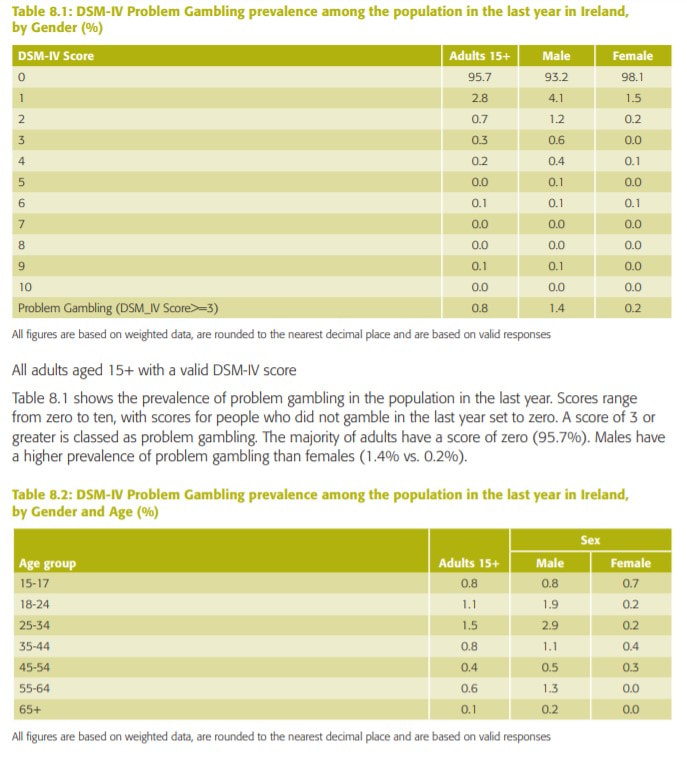

Conor Keogh: It is firstly important to consider that the above figures are not a statistical aberration and are generally in line with trends that are being seen all over Europe. Indeed, the ESPAD results found that of all those respondents across the full European sample who had gambled in the last twelve months, around 5% of respondents met the criteria for problem gambling. This equates to a rate of around 1.4% across the total sample in Europe. As has been in the case in various previous research findings, the ESPAD report also points to a very prominent gender discrepancy that exists in respect to problem gambling. In every country surveyed in the ESPAD report, boys were more likely to be problem gamblers than girls (boys had an average of 29%, compared to 15% amongst girls). Going back to the Irish context, the 2014 / 2015 Drug Prevalence Survey carried out by the National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol (NACDA) was amongst the first prevalence surveys carried out in the country to gauge gambling behaviours across the population. The report estimated that 0.8% of the male population aged between 15 and 17 fit the criteria for being problem gamblers (based on the DSM-IV classification framework). For females of the same age bracket, the figure was slightly lower, estimated to be around 0.7%. Overall, male adolescents were more likely to have gambled at least once over the past 12 months (29.9%) compared to adolescent females (20.6%). The recently released ESPAD statistics surrounding underage gambling in Ireland paint a highly dangerous picture. The ESPAD survey report (which covers a wide range of adolescent behaviours including alcohol, drug, and technology use) suggests that the problem gambling rate amongst Irish adolescent males has in fact risen to 1.7%, compared to the 0.8% found in the NACDA report. This represents nearly a doubling of problem gamblers amongst this demographic. 15 – 16-year-old females were estimated to have a lower rate, estimated to be at around 0.2%. This is in line with the average across all age-groups in the female population (0.2%), based on the NACDA 2014/15 study. In line with the other European states, boys who gambled had a higher problem gambling rate (7.6%) than the girls who gambled (2.8%). Of the students who gambled in the last 12 months, 26.3% (around 1 in 4) felt they needed to bet and spend more, and 12.2% (around 1 in 10) had lied to those close to them about their gambling behaviours. In the UK, we see a similar situation. The Gambling Commission’s 2019 report that investigated gambling behaviour amongst 11–16-year olds found that 1.7% of this demographic fit the criteria for being problem gamblers. In terms of total figures, this means that approximately 55,000 children are classified as problem gamblers in England, Scotland, and Wales. In addition to this, another 2.7% presented as being ‘at-risk’ gamblers, presenting with signs that they could be at risk of developing a more serious problem. Overall, 39% of the full cohort of respondents aged 11 – 16 have admitted gambling with their own money recently, with the most popular form of gambling being fruit machines at arcades and pubs (incidentally, slot machines were the least favoured form of gambling amongst Irish adolescent gamblers, according to the ESPAD data). Gambling amongst adolescents: new forms of gambling Decades of technological advance have meant that gambling has spread into various diverse forms of media, which has meant that the lines which demarcate what exactly constitutes “gambling” have become blurry in recent years. Such recent technological advancements have meant that gambling can be seen in increasingly common places, exposing children to it on a very regular basis, via television, mobile phones, and increasingly, in video games. One of the most notable places we can see this is through the increasingly popular “loot boxes” in video games. Indeed, recent research published by Central Queensland University found that of the 82 best-selling video games available, 62% (51 of them) had loot box mechanisms in them. For example, “FIFA packs” (as one example of many more) have been a notable demonstration of the muddied definitional lines between what is a harmless, fun feature of a game, and what is considered gambling. In many ways, the process of opening a pack (or any other similar loot box) is very much psychologically akin to a gamble and involves stimulating the brain in the same way that any other gamble does. As Macdonald (2018) says; “the dopamine hit is enjoyable, but potentially addictive, and hard to resist”. Whilst technically the reward being received by the player is not physically tangible (one might ‘pack’ a Lionel Messi in FIFA, yet this Messi has little to no value outside the game world), the overarching mechanism remains the same – it is a game of chance, of risk and reward, and is ultimately psychologically akin to real-life gambling that provides a “‘ripe breeding ground’ for the development of problem gambling among children”(Drummond and Sauer, 2018). In a recent Oireachtas report, Hurley (2020) mentions that at the time of writing, Ireland does not have a “gambling regulator, a digital safety commission or any other independent expert body responsible for determining whether loot boxes ought to be regulated as a form of gambling” and argues that there is a “growing consensus” that such regulation is required in Ireland to regulate for such practices. For many adult problem gamblers, their first exposure to gambling was in childhood. Testimonies from gamblers tell us that this first exposure can range from anything like buying a scratchcard, betting on the Grand National, sneaking into a casino, or perhaps playing cards with friends. Now, the number of opportunities available to would-be adolescent gamblers is enormous. This, combined with a very-liberal approach to gambling advertisement (noticeably during live sports), a prominent “gambling culture”, and the emergence and popularisation of gambling-simulator type practices in more common forms of media (such as video games), has led to a situation where children and adolescents have become at great risk to the harms associated with gambling, and the recent ESPAD statistics are a distinct testament to this. Problem gambling comes with a devastating personal, economic, psychological, and social cost. The figures that we see here from ESPAD are a result of an industry that has been continually under-legislated for in Ireland, and are a stark indictment of the Government’s failure to implement any meaningful legislation or solutions in order to counterbalance the devastating personal, financial and social cost of a gambling addiction. They also act as a timely reminder (and warning) that not enough has been done to protect children and adolescents from the harm associated with gambling, and that there is an urgent need for the development and implementation of proper channels of gambling prevention education, support, and treatment in Ireland, along with re-emphasising the urgent need for across-the-board legislation. NACDA Problem Gambling Prevalence Survey 2014/15

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|